Our primary objective is to institutionalise balance and strengthen our institutions

The Daily Star (TDS): How do you evaluate your commission's work—was it more of a complete rewriting or a revision of the Constitution of Bangladesh?

Ali Riaz (AR): The Constitution Reform Commission has been entrusted with two key responsibilities. The first is to review the current Constitution, which, as observed by the public and civil society, contains numerous flaws. The most significant shortcoming is the failure to realise democratic aspirations. Instead, autocratic tendencies have repeatedly surfaced, becoming particularly dominant over the past 16 years.

The second responsibility is to propose necessary reforms to democratise the Constitution. Accordingly, we have put forward recommendations focusing on the executive branch, the legislature, and fundamental human rights. Now, it is the responsibility of political parties to implement these suggestions, while our commission's role was not to rewrite, revise, and amend the Constitution.

During the press briefing on November 3, we explicitly stated that our work involves revision, removal, and addition. However, the extent to which these recommendations will be executed ultimately depends on the political parties.

TDS: You introduced new principles in response to recent uprisings, marking a departure from the 1972 Constitution. What necessitated these amendments to its original principles?

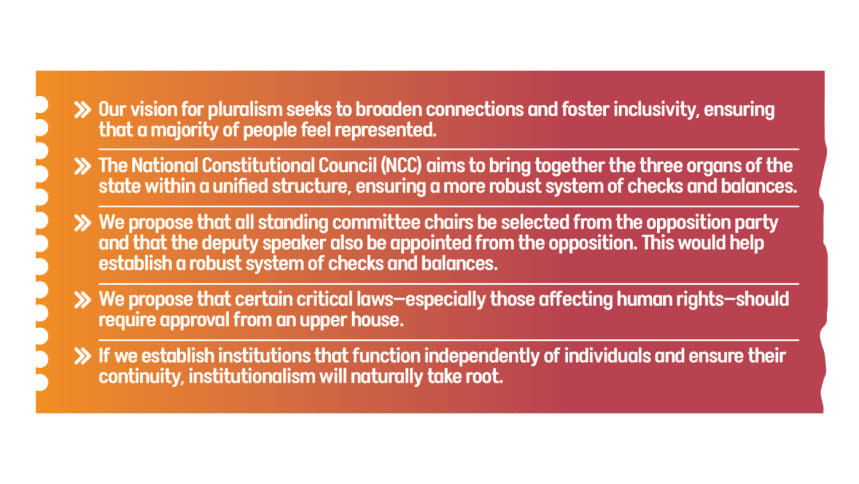

AR: The promises of the Liberation War of 1971—equality, dignity, and social justice—were reflected in the Proclamation of Independence. These ideals should have been enshrined in the Constitution of 1972, though they were not fully incorporated at the time. Importantly, these promises form the foundation of the state, and we believe it is essential to return to them, as 1971 remains the source of our collective identity and aspirations. These three principles are not only the bedrock of the state but also a concrete expression of the people's aspirations, born out of a long history of struggle. We firmly believe these ideals should form the foundation of the Bangladeshi state. The aspiration for democracy, embedded in the Constitution of 1972, remains unquestionable. Over the last 16 years, particularly during the movements of July and August, the masses have resisted overwhelming oppression in their fight for democracy. This enduring spirit of struggle has been incorporated into our proposal. In addition, we have emphasised the importance of pluralism. To create an inclusive society and state, we must first embrace diversity, allowing for multiple voices and paths. For instance, we must include marginalised groups such as Dalits and the third gender. Similarly, within religions, there are various sects that must also be acknowledged. Bringing together these diverse groups under one unified state is essential. Our vision for pluralism seeks to broaden connections and foster inclusivity, ensuring that a majority of people feel represented. The ongoing discussions about the principles of the state are highly positive, as they aspire to return to the spirit of 1971 while upholding democracy. Such discussions are crucial, especially given the lack of meaningful dialogue over the past 53 years. What we have proposed are merely suggestions—the rest will depend on the decisions of political parties and members of civil society.

TDS: Your proposal has faced criticism regarding the exclusion of secularism—how do you ensure pluralism without it?

AR: If you examine secularism academically, you will find that its ideas and forms have evolved significantly, accompanied by discussions on its limitations. Another crucial factor is the political reality. Over the past 53 years, secularism has, at times, led to confusion and been used as a tool for repression, raising the question of how best to navigate these complexities.

In response, we have integrated academic critiques with the aspirations of the people gathered through discussions. We believe it is essential to broaden participation in these conversations, moving beyond the traditional focus on the relationship between the state and religion or between religion and society. Instead, we advocate for expanding these discussions to embrace greater inclusivity, recognising that pluralism and secularism are not entirely separate. Rather than treating secularism as a problem, we should explore ways to strengthen and foster inclusiveness within these critical debates.

TDS: How did your commission navigate reform decisions—such as adopting a proportional election system—when even key political parties struggled to reach a consensus?

AR: We did not engage in direct discussions with political parties but consulted civil society members, various socio-cultural and professional organisations, as well as legal and constitutional experts. Political parties shared their views in written form, along with inputs from many others, all of which we carefully considered. Our work aimed to democratise the process and reduce the centralisation of power in a single individual—principles rooted in the ideals of the 1971 War of Liberation—to uphold citizens' rights. We gathered perspectives from relevant groups and incorporated our own insights, as the nine commission members have extensive experience working on constitutional matters. With these collective inputs, we sought to reach this point.

TDS: One of the key focuses of your recommendations is to curb the Prime Minister's overwhelming power. How do your proposed provisions address this issue?

AR: Our suggestion is that in a Westminster-style parliamentary system, the Prime Minister will inevitably hold some powers, as the PM is selected by the ruling party based on the confidence of the majority members in parliament. However, there must be a mechanism to check and limit the Prime Minister's authority. The challenge, which has been debated for the past decade, is how to establish this balance effectively.

A common perception is that transferring some of the Prime Minister's powers to the President could create equilibrium. However, this approach presents two key issues. While such a shift may appear to establish balance, there is no guarantee of its effectiveness, as the Prime Minister and the President are not merely individuals but institutions. Democracy functions through institutions, not individuals, which is why our focus is on institutional reform.

To achieve this, we have proposed a balanced framework, most notably through the establishment of the National Constitutional Council (NCC). This council aims to bring together the three organs of the state under a unified structure, ensuring a more robust system of checks and balances. In our experience, the relationship between the ruling party and the opposition has always been overwhelmingly bitter. However, a democracy cannot function effectively under such circumstances. Looking ahead, we expect a more cooperative and balanced political environment. With this in mind, we have considered the three organs of the state, ensuring that they operate with greater coordination and discussion.

Additionally, we propose granting some authority to the President. At present, the President cannot act without the Prime Minister's recommendations, but our proposal allows the President to exercise certain powers independently. Moreover, our focus extends beyond the executive branch—we have also outlined measures for the legislature. Specifically, we propose that all standing committee chairs be selected from the opposition party and that the deputy speaker also be appointed from the opposition. This would help establish a robust system of checks and balances.

For instance, in matters of declaring a state of emergency, the current system places this decision solely in the hands of the Prime Minister. We recommend that such a decision be made by the National Coordination Committee (NCC) instead, ensuring broader consultation and consensus. While emergencies may arise in certain situations, their declaration should be a matter of collective discussion. Our primary objective is to institutionalise balance and strengthen our institutions.

TDS: How would your proposed bicameral parliament enhance legislative accountability?

AR: The concept of a bicameral system emerged from two key considerations. First, in our current parliamentary process, even in the most credible previous election, parties came to power with only 40-41% of the total vote. This means a significant portion of the electorate—those who did not vote for the ruling party—remains unrepresented. These individuals are citizens and voters who supported other parties that failed to secure victory. The question, then, is how to ensure their voices are heard. Our goal was to address this issue and provide a mechanism for their representation.

Second, a brute majority or a two-thirds majority in parliament allows for the passage of any legislation without sufficient checks. This creates the risk of laws being enacted that could undermine fundamental rights. To prevent such occurrences, we proposed that certain critical laws—especially those affecting human rights—should require approval from an upper house. However, budgetary matters should remain under the jurisdiction of the lower house.

In essence, we believe this system would create a necessary balance. Given our current political reality, we must find a solution that ensures fair representation and safeguards against unchecked legislative power.

TDS: How would your proposed guidelines strengthen human rights protection?

AR: Now, rights are divided into two forms: basic rights and citizens' social and economic rights. What we consider is that these rights must be ensured. Economic rights cannot be ensured overnight—for instance, the right to food for all. Therefore, we have stated that these rights should be progressively ensured based on the state's capacity.

In the Constituent Assembly debates of 1972, it was discussed that economic rights should have been ensured. However, the country lacked the capacity at the time, as it was devastated by war and everything was just beginning. But now, we are not in the same position. Although we still cannot do everything, we can meet the demands of some of these rights.

Some rights, however, are basic and must not be denied. No one should be left without protection, and fundamental rights, such as the right to vote, must not be taken away for disappearance. We have also emphasised the importance of ensuring the rights of future citizens. Now, we exist in this universe as custodians of future generations. While we use nature, it must be protected.

TDS: What would be the role of National Constitutional Council (NCC)?

AR: We intended to structure it so that the three organs of the state could sit together to discuss any matter. However, now discussions can only take place in parliament, and our experience has not been satisfactory. There should be a dedicated platform to deliberate on laws, the future, and various state affairs.

We proposed that appointments to constitutional bodies should be made by the NCC. We observed that when such decisions depend on individuals, personal preferences take precedence. Instead, we want these appointments to be made institutionally.

The NCC consists of the president, prime minister, leader of the opposition, chief justice, and speaker. Within this framework, they can discuss and resolve matters in a way that benefits citizens and the nation as a whole. If we establish institutions that function independently of individuals and ensure their continuity, institutionalism will naturally take root.

TDS: Your proposal requires a two-thirds parliamentary majority and a referendum for constitutional amendments, making changes more challenging for political parties. What is the rationale behind this?

AR: The fundamental principle is that citizens must have a say in any constitutional amendments. The constitution exists for the people and serves as their protector. Without incorporating their views, amending the constitution is unacceptable.

We have witnessed how the 15th Amendment significantly curtailed the people's power to vote. A core democratic principle is that governance must be based on the people's consent. Elections serve this purpose—political parties reach out to citizens, gather their views, and, through the voting process, secure their mandate to govern.

We have also proposed a four-year parliamentary tenure. The idea originated from recommendations by various political parties and civil society members. History shows that prolonged power often leads to abuse. Therefore, we advocated not only for a four-year term for Parliament but also for all constitutional commissions to prevent potential overreach and ensure accountability.

TDS: How optimistic are you about a change in political culture?

AR: Our past may be bleak, but that does not mean our future is destined for frustration. I believe political parties and political culture will continue to develop from this point forward.

My optimism stems from witnessing this recent uprising. Will we not learn from this event? Of course, we will. However, I am also realistic—I do not expect political parties to change overnight, as that would be utopian. A written constitution can establish institutions and provide guidance, but it alone is not enough—it must also cultivate an environment where a healthy political culture can thrive.

None of us are perfect, but we can now express our aspirations. Naturally, not everyone's desires will align—some will share common ground, while others will differ. Yet, it is crucial to voice our thoughts, as such space for expression was previously nonexistent.

Politicians are part of our society; they remain connected to the people and understand their thoughts and expectations. Ultimately, the success of our initiatives will hinge on public consensus. I remain hopeful—when discussing politics, we find many shared perspectives. If we can foster a space where politicians align with public sentiment and receive broad support, meaningful change can be achieved.

News Courtesy:

The Daily Star | February 27, 2025